The Grand Anicut, Disastrous Rise Of TB And HIV Cases, Postage Stamps

Along-with cartoons and recommendations

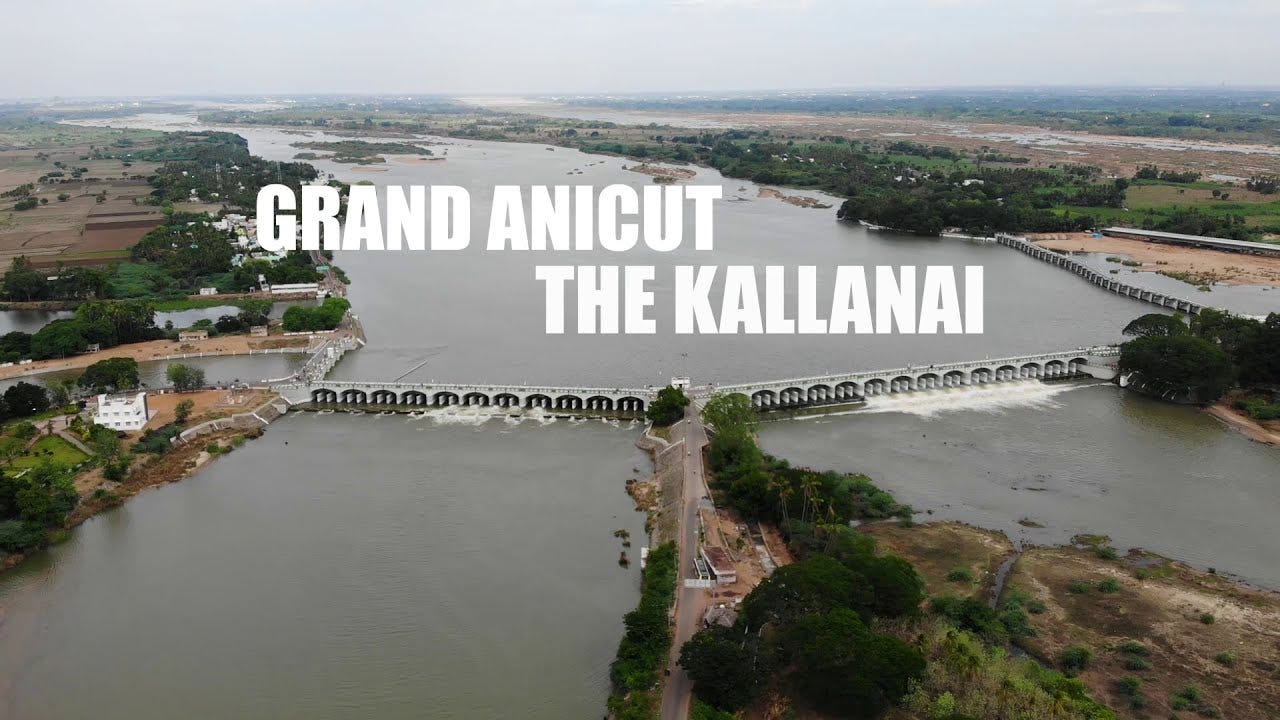

The Grand Anicut, also known as the Kallanai, stands as a testament to the engineering ingenuity and foresight of ancient India. Constructed by the Chola king Karikala Chola around the 2nd century CE, this dam is not only one of the oldest in the world but also a symbol of the advanced understanding of water management that flourished in Tamil Nadu over 1,800 years ago. […] King Karikala Chola, a ruler of the early Chola dynasty, is credited with the construction of the Grand Anicut. His reign is often celebrated for its emphasis on infrastructure development, particularly in the areas of agriculture and irrigation. The Kaveri River, which flows through the fertile plains of Tamil Nadu, was both a blessing and a challenge for the people of the region. While the river provided much-needed water for agriculture, it also posed risks of flooding, especially during the monsoon season. King Karikala’s vision was to harness the river’s potential while mitigating the dangers it presented, leading to the construction of the Kallanai.

[…] The most remarkable aspect of the Grand Anicut is its longevity. Despite being nearly two millennia old, the dam is still in use today, a testament to the durability and effectiveness of its construction. The dam has undergone several modifications and reinforcements over the centuries, particularly during the British colonial period, but the core structure remains as it was during King Karikala’s time.

Why Are We Talking About A Structure Built Two Centuries Ago?

The following excerpts are from recent news alerts:

"The 35-feet Shivaji Statue inaugurated by Narendra Modi collapsed today. It's a reflection of the poor quality of infrastructure built by Modi sarkar. Shivaji was a symbol of equality and secularism, his statue's collapse is an example of Narendra Modi's lack of commitment to Shivaji's vision," Asaduddin Owaisi posted on X.

Bike Rider Rescued After Road Collapse Amidst Heavy Rain in Gurugram (Gurgaon was recently renamed to Gurugram by BJP CM Khattar)

A roof collapse at New Delhi's main airport highlights Prime Minister Narendra Modi's challenges to make India a global aviation hub and raises questions about the rapid pace of infrastructure development in India.

The 755-foot-long pedestrian bridge, built during the Victorian era, had long been a tourist attraction, and it was packed with people as the sun set on Sunday and the intense heat eased. As countless others had done before them, some on the span spread their arms across its four-foot width, grabbing the green netting on either side and making the bridge shimmy from side to side.

Then, suddenly, the cables snapped, and the bridge spilled its human cargo into the river, like a fishing net releasing its catch. Once in the dark water, some tried to swim to the fallen structure and climb up its tangled netting. Others were swept away.

After the deaths of at least 134 pedestrians, the country is asking why its infrastructure has failed so calamitously once again.15 engineers suspended in Bihar after 12 bridges collapse in over two weeks

Less than two years after it was inaugurated, the much-touted Pragati Maidan tunnel is marred by seepage, cracks and waterlogging, with the PWD even declaring it a ‘potential threat to passengers’ (inaugurated by PM Modi himself with his famous all-by-himself walking across empty roads and waving at camera PR video)

Water leak spotted in new Parliament building, ‘paper leak outside, water leakage inside’, says Congress MP

Designed by Ahmedabad-based HCP Design, Planning and Management, the building was constructed by Tata Projects Ltd at an estimated cost of Rs 1,200 crore.

TB Cases Are On The Rise

Five years ago, Mr Narendra Modi promised “to eradicate the disease in the country by 2025”. We are only months away from his promised dawn. But things, instead of getting better have only got worse. And patients along with healthcare workers blame it on government policy.

In 2023 alone, over three hundred and twenty thousand Indians died of tuberculosis—a curable and preventable disease—accounting for over a quarter of the global mortality figures. Today, thanks to rampant misgovernance, India’s 2.8 million tuberculosis patients struggle to access the drugs that would save their lives. “It is like we have learnt nothing from COVID-19,” Ganesh Acharya, a tuberculosis survivor and activist, told me. “We are in a public-health emergency of genocidal proportions. It sounds like an exaggeration, until you look at the number of people dying.” Two separate epidemiologists used a different term: policide, or death by policy.

A hallmark of India’s failure to control tuberculosis—one that should define the Modi years, much like Thabo Mbeki’s government in South Africa is remembered for its AIDS denialism in the early 2000s—is that politics has trumped science, as well as humanity, every step of the way. The Modi government’s flagship tuberculosis control policy, the Pradhan Mantri TB Mukt Bharat Abhiyaan, creates a medical dystopia in which corporations, non-profits and individuals are invited to “adopt” patients. By pledging support for up to three years, the donors, known as Ni-kshay Mitras, can get themselves photographed handing food baskets to patients. “TB has so much stigma, and the government is using patients as props for photo-ops,” Acharya said. “It is so humiliating.”

“Everything has become a photo-op for some director of some company, without any care for how patients are being robbed of their dignity,” a tuberculosis researcher told me, on condition of anonymity. “This is an infectious disease. Confidentiality has to be maintained. Historically, Indian governments have implemented food delivery schemes without this tacky photo app.”

Even as it abdicates its responsibility to provide nutritional support to tuberculosis patients, the government has also failed to provide them adequate healthcare. Despite Modi’s rhetoric, patients are staring at a cataclysmic tragedy: older drugs are out of stock, while newer therapies are not being approved. […] In April this year, with the campaign for the general election in full swing, Maharashtra, the hottest of the world’s tuberculosis hotspots, had only fifteen days’ worth of medicines left. By July, Blessina Kumar, the CEO of the Global Coalition of TB advocates, told me, the Champaran region of Bihar had completely run out. Doctors were left with the impossible task of rationing drugs among patients, who were, in turn, skipping doses to make their precious allotments last longer. When patients miss doses, it boosts antibiotic resistance in the community, turning a treatable disease into a nastier, drug-resistant version. India has the world’s highest burden of people with drug-resistant tuberculosis: nearly a hundred and twenty thousand, as of 2021.

Tuberculosis and HIV—two of the deadliest killers known to humanity, having killed more people than the two World Wars put together—are an efficient tag team. At the height of the AIDS epidemic during the 1990s, they came to be known as the “cursed duet,” as patients with HIV began dying of tuberculosis. If you are infected by HIV, you do not die of HIV. By switching off the body’s immune system, the virus creates an opportunity for other diseases to plunder the body through “opportunistic infections.” Tuberculosis is the leading opportunistic infection among HIV patients. People living with HIV are around twenty times as likely as others to contract tuberculosis.

Both HIV and Mycobacterium tuberculosis are master mutators. They have lengthy periods of latency, during which they lie low and wait for immunity to be depleted. Neither pathogen kills its host immediately, which is a huge evolutionary advantage that allows the disease to spread. This makes disease surveillance, forecasting patients’ medical needs and establishing trust among the community critical.

In 2022, the HIV-positive community faced stockouts similar to the ones tuberculosis patients are currently experiencing, with at least half a million people reportedly struggling to access antiretroviral drugs. Patients protested for over three weeks in front of the health ministry, which denied the shortage. Sujatha Rao, a former health secretary who set up India’s HIV programme during the 1990s, told me that the stockouts took place because “the government messed up the procurement cycle.” Rao recalled being told that a bureaucrat in the ministry “sat over” the tendering process, causing delays. “It is important to do the boring stuff well, like inventory and forecasting,” she said. “I used to constantly monitor it and maintain a three-month stock. These are not paracetamol tablets that you can buy in a pinch from the market when you run out.”

The HIV programme was one of India’s more successful public-health interventions, halting the progress of an epidemic that was devastating the developing world. The secret to the success was prevention. Advertisements promoting safe sex were common on television, celebrities such as Shabana Azmi attempted to destigmatise the infection and sex workers collaborated with the health ministry to advocate for condom use.

Since Modi came to power, the entire approach to infectious diseases has radically changed. In June 2014, the health minister at the time, Harsh Vardhan, controversially argued that fidelity in marriage was more important than condom use in preventing AIDS and proposed a ban on sex education in schools. “There is a conservative attitude, and the systems that were laid down are not being used,” Rao said. “Advertisements promoting condom use, safe sex, et cetera, have completely disappeared from public discourse. Everything is about Ayushman Bharat and insurance coverage. Insuring people is not adequate for public health.” Around 2.4 million Indians now live with HIV. In 2022, there were around sixty thousand new cases and over forty thousand deaths—most of them from tuberculosis.

While the Modi years will be remembered for catastrophes such as demonetisation, the migrant crisis during COVID-19 and the abrogation of Article 370, it is his health policy that will cast the longest shadow over future generations. Even as millions of people continue to be infected by tuberculosis and HIV, the media and the government have been fixated on the blood sport of election campaigns. “There was a time when TB did get some attention in terms of money but, post COVID, we seem to have no interest in solving the real issues,” Yogesh Jain said. “It is all about the optics.”

“Instead of eliminating TB,” Ganesh Acharya said, “the government is eliminating us.”

— Death by Policy: The Modi government’s catastrophic failure to control tuberculosis

What To Watch

Paheli

I saw Paheli a few months ago and was quite happy watching it. Then I stumbled upon this Reddit post.

I was watching “Paheli” again a few days ago. Always loved the movie. It’s really well shot, colourful, and extremely detailed in terms of capturing the various nuances of Rajasthani culture. Every character is so well defined to fit into the cultural ethos perfectly. One of the finest roles by SRK, completely restrained and a delightful Rani Mukherjee, showing vulnerability and boldness in equal measure.

There’s more written by this Redditor here but first, please watch the movie.

My God, the visuals!

First things first, this is the best-looking Indian film in a very long time, and ranks up there with the finest ever. Amol Palekar has crafted a delectable fairytale that is incredibly well-shot. Ravi K Chandran's cinematography is spellbinding as he casts us into the fabulous sandscapes of Rajasthan with fluid harmony. Each frame of the film is picture-perfect, marinated in intoxicating colour.

Watching Paheli is quite an experience, and it's from the very opening shot of the film that its sheer, magical palette overwhelms us.

— rediff.com

Angry Young Men on Prime

This show is so damn good.

Myths of Homeopathy

Medical professional, writer, activist, Dr Shantanu Abhyankar passed away recently. He wore many hats and was many things to many people but what really interested me was him starting out as a homeopathy doctor and then realising the fraud, switching gears and going back to school and becoming modern medicine doctor. You will like to watch his TED talk below.

Aamir Khan Chatting With Rhea Chakraborty

I can’t remember Aamir being this open in any interview before. And good to see Rhea after all that assassination of her life and career by Indian media.

Do You Remember Postage Stamps?

As some of you might know, prior to the 1840s, sending a letter was a gamble. Or even a nightmare. Postage was calculated by distance and number of sheets, and recipients often ended up paying exorbitant fees. The recipient, not the sender, often bore the cost, leading to arguments and rejected deliveries. Enter a British schoolmaster, Sir Rowland Hill (1795-1879). Hill wasn’t your typical revolutionary. By day, he was a schoolmaster with a passion for education reform. But his frustration with the snail-paced, ridiculously expensive postal system propelled him into becoming the father of the modern postal service.

Legend has it that the sight of a poor woman refusing a delivered letter due to the cost of postage sparked Hill’s outrage. Hill’s solution was as simple as it was ingenious: a uniform penny postage rate based on weight, prepaid by the sender. He tirelessly campaigned for his idea, publishing a pamphlet titled “Post Office Reform” in 1837. The establishment, however, wasn’t convinced. They worried about forgery and a drop in revenues.

Here’s where things get interesting. While pondering prepayment solutions, Hill initially proposed stamped envelopes. But a printer named James Chalmers suggested a small adhesive label which Hill readily adopted (the invention of the world’s first adhesive stamp is actually a widely debated matter, but for the sake of brevity and convenience let’s stick to this version). Thus the iconic Penny Black, featuring a profile of Queen Victoria, was born in 1840, forever changing how we communicate.

Hill’s reforms were a giant success. Mail volume skyrocketed, communication boomed, and the government even saw increased revenue. Hill, finally recognised for his genius, was knighted by Queen Victoria and became a national hero. Rowland Hill’s legacy extends far beyond the Penny Black. His vision of a cheap, efficient, and accessible postal system became the blueprint for postal services around the globe.

Interestingly, the Penny Black wasn’t just a marvel of convenience; it was a cornerstone of nation-building. Queen Victoria’s stern visage on the stamp served as a constant reminder of the vast British Empire the mail traversed. Soon, stamps became miniature ambassadors. New nations declared their independence by featuring their own landscapes, flora, and fauna. Tiny island nations, like Nauru, with limited resources, used vibrantly coloured stamps to attract tourism and collectors, their postage functioning as a miniature marketing campaign.

[…]

Back in India, the region saw its first stamp in 1852. According to India Post, these circular stamps were individually embossed onto paper and had the words “Scinde District Dawk” (postal system of runners serving Sindh region, now in Pakistan) printed around the rim and the East India Company’s Merchant’s Mark as the central emblem. The First Stamp of independent India was issued on November 21, 1947. It depicts the Indian Flag with Jai Hind (Long Live India) in the top right-hand corner, valued at three and one-half annas. In India, as elsewhere, stamps have captured poignant moments in history. They have served as tools for national integration and literacy campaigns, they instil patriotism, celebrate inclusivity, empower women, reflect wars, and more.

— Frontline (Elections on postage: A journey into history)

That’s it for this one.