Nehru, Resistance Of Madiga Women In Karnataka, Poem on Cats and Update On Palestine

A Man of His Time

What we talk about when we talk about Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru is back in the Lok Sabha. He may have passed away nearly sixty years ago, but his ghost haunts India’s political discourse. The first prime minister and his legacy are often at the centre of today’s political debates. […] Nehru has often been accused of fostering a cult of personality. The development of such a personality involves elevating one man above others and imbuing his leadership with a mystical air. The cult requires strict regulation of the production of imagery about the leader, and the ruthless demand for loyalty. A measured evaluation of his premiership reveals that Nehru actively avoided this enterprise. […] Indeed, in 1957, when he was approached with the idea for a book of extracts from his speeches, titled “Nehru’s Wisdom,” he dismissed the title as “pompous.” Nehru could have had his own “little red book,” several years before Mao Tse-tung, but he declined the proposal.

[…]

Firstly, far from being an era of ideological conformity, the Nehru years were an age of experimentation. In these experiments, Indians engaged all the tools of mid-twentieth-century social science: they started with small, pilot projects; after evaluations, adjustments were made, and the programme was rolled out on a larger scale. After the Constitution was promulgated, there were very few big-bang all-India policy changes. The Planning Commission, rather than acting as a Soviet-style command body, was important in overseeing these pilot projects and evaluating the progress of various programmes. This experimental attitude covered nearly every area of government policy, from village food production to international relations.

Secondly, rather than micromanaging everything, perhaps the most important role Nehru played in the young country might be encapsulated in the idea of the patron. One of the ways in which Nehru shaped postcolonial India was through supporting projects that were proposed by energetic people around him. From SK Dey, who pioneered India’s community development projects, to Durgabai Deshmukh, who founded the Central Social Welfare Board to provide some of the country’s first welfare programmes, brilliant men and women who had earned the prime minister’s respect and esteem were given encouragement and support to pursue their own experiments in postcolonial India. […]

Thirdly, India in this period developed its own internationalism, which had a number of facets. To begin with, Nehru and his rather large team of often unruly diplomats, developed a shared vision for an international order that centred around unwinding imperialism and its legacies. Their programme included promoting peace by helping establish a rules-based international order. It was unique for the attention it paid to people, including minorities, in international politics. Indian internationalism was both more creative and more ambitious than non-alignment. […]

Indian internationalism was ambitious because the country regarded itself as a leader in the decolonising world. India sought to spread the knowledge gained through its experiments to other parts of Asia and Africa. It seemed to seek a leadership role on as many UN bodies as possible. Hansa Mehta helped draft the Universal Declaration on Human Rights, and when she departed Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay took her place. Ramaswami Mudaliar and Palamadai S Lokanathan, were respectively the first president of the Economic and Social Council and the first executive secretary of the Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Far East. Rajkumari Amrit Kaur represented India as a founding member of the World Health Organization, and the physicist Homi J Bhabha presided over the first UN Conference on Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy. Lesser-known Indians occupied 84 of 136 places in the UN Technical Assistance Administration by 1952. Indians were counselling and advising countries on building everything, from multipurpose dams to democratic institutions, with all the mixed results one has come to expect of mid-twentieth-century development strategies.

— The Caravan Magazine

But marginalised communities have resisted this too. […] In 2002, a few Madiga women—classified as SC in Karnataka—from Raichur district’s Lingasugur village began organising an Okutta or confederation to fight the devadasi system, a caste-based practise imposed by dominant castes through Hindu temples. The Okutta led by Dhyamamma Rampur, Akkamma Bhogapur and Moksha, among others, was radical in its organising—they gheraoed the Raichur district collector’s office and organised months of silent sit-ins until their demands were accepted. Their early victories accorded former-devadasis in the region with monthly pension, work cards, access to education for their children and a separate budget for welfare activities.

Over the years, the Okutta fought back against feudal landlords and even took on the illegal liquor mafia. Simultaneously, it branched out into newer formations including a union of farm workers which fought for fair wages, ensuring that wages were not eaten up by contractors and the equal distribution of work under the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act. When they faced opposition and crack-downs from dominant caste panchayat leaders, the Okutta stood for elections under the new banner of GKKS. It was wildly successful, contesting more than seven hundred panchayat seats, against all three major parties in the state, and winning more than five hundred and fifty.

It was evident when I met a group of GKKS members in the village of Jagir Venkatapur, that their struggle is an uphill one. Pointing to the well down the road, Sasikala, one of the three GKKS candidates who won panchayat elections in the village, told me, “We Madigas still can’t draw from that well, only the Kurubas and Kabhers can.” Suneeta, the youngest of the three, responded, “This is how it has been.” But she quickly added, “things will change.”

— All Santhosh’s Men: The BJP’s re-engineering of Karnataka

Are You Getting Enough Sleep?

… sleep patterns vary quite a bit across countries with some countries sleeping as much as an hour more per night than others. The best sleepers tend to be in northern European countries. So that includes Estonia, Finland, Ireland, and the Netherlands and also Australia, and New Zealand. So people in these countries all average about seven hours of sleep a night and the worst sleepers tend to be in Asian countries.

So Japan and South Korea ranked at the bottom and this isn't because people in Asia are early birds. They tend to wake up around the same time as people elsewhere. But rather because they go to bed about 35 minutes later.

… the sad thing is that the countries that log the fewest hours of sleep a night also tend to have the worst quality sleep. So previous research has shown that when people are given a shorter window of time to sleep; so when they're kind of restricted in the times that they sleep, they actually tend to sleep better but this study found the opposite. The data showed that people in Asia not only went to bed later and slept less. They also tended to have lower-quality sleep, meaning they spent more time, tossing and turning and slept less consistently. Uh, what's more, you might expect that less sleep during the week would naturally lead to more sleep on weekends. But in fact, Asians tend to enjoy less of this kind of catchup sleep on weekends than Europeans, for example.

Listen in below from 20:00 for more.

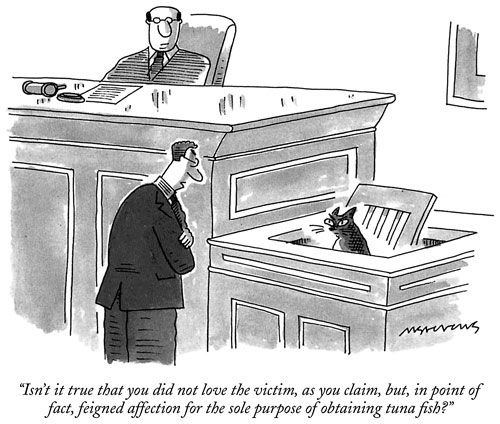

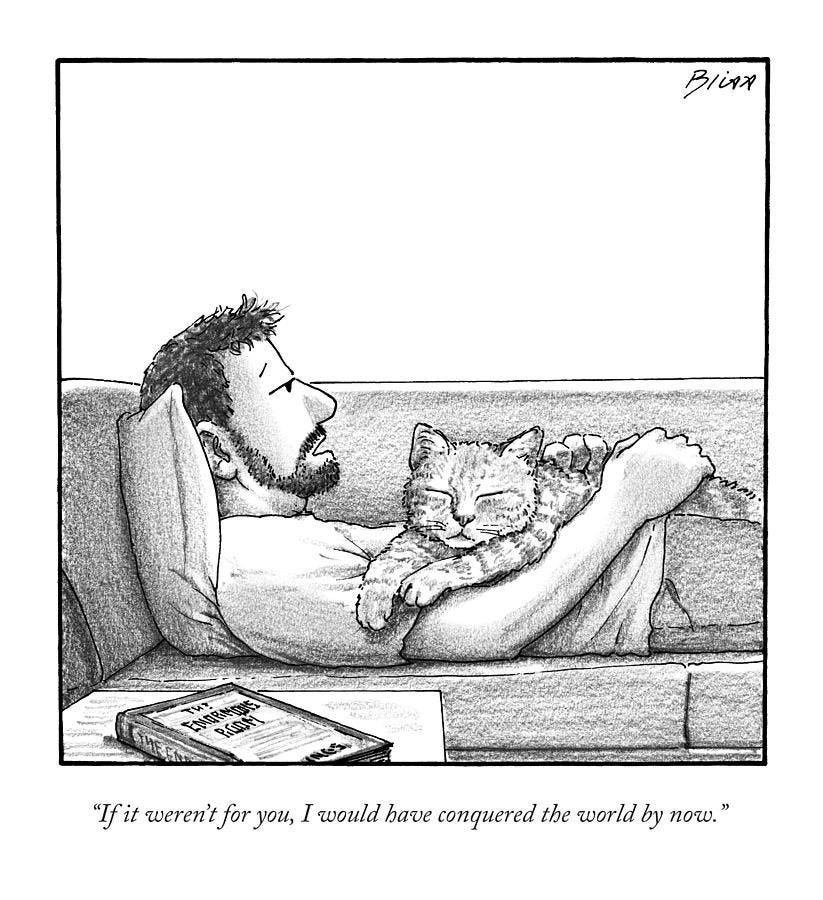

My Cats by Charles Bukowski

I know. I know.

they are limited, have different

needs and

concerns.

but I watch and learn from them.

I like the little they know,

which is so

much.

they complain but never

worry,

they walk with a surprising dignity.

they sleep with a direct simplicity that

humans just can't

understand.

their eyes are more

beautiful than our eyes.

and they can sleep 20 hours

a day

without

hesitation or

remorse.

when I am feeling

low

all I have to do is

watch my cats

and my

courage

returns.

I study these

creatures.

they are my

teachers.

SATINDER KUMAR LAMBAH, the Indian high commissioner to Pakistan, faced “one of the most difficult days” of his career when the Babri Masjid at Ayodhya was destroyed by workers of Hindutva organisations in December 1992. The storied diplomat, much loved and respected in Pakistan, would have become persona non grata had it not been for Nawaz Sharif, Pakistan’s prime minister, and a close friend of Lambah’s. However, what stands out today is Lambah’s response to the criticism in Pakistan of India’s treatment of Muslims after the demolition.

Lambah had several conversations with journalists and other important Pakistanis, highlighting the “outstanding contribution” of minorities in India, according to his memoir, In Pursuit of Peace: India-Pakistan Relations Under Six Prime Ministers. In one interaction, which included former senior Pakistani military personnel, Lambah emphasised that during the 1971 Bangladesh war, Sam Manekshaw, a Parsi, was the Indian Army’s chief; Jagjit Singh Aurora, a Sikh, was leading the force’s eastern command; and JFR Jacob, a Jew, was the command’s chief of staff. “This, I added, was not by design but the result of the normal functioning of the Indian Army, a matter of pride for every Indian,” Lambah writes.

Even at the political level, the foreign minister was a Sikh (Sardar Swaran Singh), the defence minister was a leader of the Harijan community (Jagjivan Ram) and the overall leadership was under a woman (Indira Gandhi). This appealed to thinking Pakistanis. One commented that while they were aware that Muslims had occupied top posts in the country, they were nonetheless impressed that a Muslim held the sensitive position as chief of air staff earlier from 1979–81. I responded this was a normal occurrence which did not surprise us, as it did our friends in Pakistan.

While his book was published this year, Lambah passed away last June, after witnessing eight years of Narendra Modi’s rule. “Unfortunately,” he writes, “the situation in India too is undergoing a change. For instance, as Indian journalist Aakar Patel points out, India does not have a Muslim chief minister in any of its twenty-eight states, in fifteen there is no Muslim minister and in ten just one, usually in charge of minority affairs. Patel called this a deliberate exclusion of 200 million people.”

[…]

Notwithstanding Lambah’s partial blindness to India’s shortcomings before 2014, his section on the Babri Masjid demolition particularly demonstrates that the rise of a government steeped in Hindutva ideology—and its diplomats behaving like representatives of a de facto Hindu Rashtra—does not bolster India’s case in foreign lands. The Modi government has weakened India’s traditional strengths, particularly in South Asia, replacing the moral high ground of progressive values with a poor caricature of China’s Wolf Warrior diplomacy. Modi’s India has neither the geopolitical nor economic heft of Beijing to achieve national aims with sharp words. The government’s statements can only make its internal constituency of Hindutva supporters, suffering from some form of inferiority complex, feel better.

— Negotiating Peace: Ex-diplomat Satinder Lambah’s lessons for Modi’s Pakistan policy

Update on Palestine

Here are the latest casualty figures as of 5:00pm in Gaza (14:00 GMT) on October 16:

Gaza

Killed: at least 42,409 people, including nearly 16,765 children

Injured: more than 99,153 people

Missing: more than 10,000

The latest figures from the Palestinian Ministry of Health in the occupied West Bank are as follows:

Occupied West Bank

Killed: at least 756 people, including at least 165 children

Injured: more than 6,250 people

In Israel, officials revised the death toll from the October 7 attacks down from 1,405 to 1,139.

Israel

Killed: 1,139 people

Injured: at least 8,730

Devastation across Gaza

According to the latest data from the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, the World Health Organization and the Palestinian government as of October 13, Israeli attacks have damaged:

More than half of Gaza’s homes (damaged or destroyed)

80 percent of commercial facilities

87 percent of school buildings

Healthcare facilities so 17 of 36 hospitals are partially functional

68 percent of road networks

68 percent of cropland

Source: Aljazeera

You Might Want To Watch

There’s a new baba in town.

This old gem from Kabir Cafe

Who knew Fareed Ayaz, the famous qawwal from Pakistan, was born in India’s Hyderabad? I found this interview on Rajyasabha TV. Watch it not just for the depth of knowledge Fareed Sahab displays but also for how the interviewer conducted it. He lets him talk and make his point but also stops him and asks follow-up questions, and when he disagrees with a point, he lets his disagreement known.

I finally saw this Marathi movie Jhimma after many recommendations. And loved it.

That’s all for this one.

I hope I was able to add some value to your understanding of the world. And something of this interested you. Do write back and suggest things to read, listen to and watch.

Do subscribe if you haven’t already so this can get delivered to your inbox whenever the next one gets published. Unlike the web version, email gets delivered each time with a new quote/poem!